A few years ago Tacey M. Atsitty (also known as Sáanii Gonzales to her friends) found herself gripping the steering wheel with all her might as her truck spun out and crashed during a snowstorm that seemed too mild for such a violent result. Her grip forced her wrist to take much of the impact. Emergency medical technicians came to her aid, as she says in her sonnet “The Night My Wrist Broke.”

All but one looked away, allowing me to cry for a moment longer, as though I were one of them. I kept my right wrist close to my chest: a pain so clear I could see every empty cavity in my ribcage, heart thumping like a bass guitar— hand strumming to the sound of a girl wailing.

Atsitty’s wrists have also suffered from the extensive use of normal life: many moves from place to place in the last several years, a sprain from an awkward throw.

As many 40-somethings acutely learn (and others, too, of course), there are many parts of our bodies that we think little of until they’re injured, and then they become an overbearing presence in their pain.

Perhaps that concept has something to do with the connection between the title of Atsitty’s latest book of poetry, (AT) WRIST, and its overarching theme of love and pain. But this isn’t a typical book of love poems. Some of the poems explore romantic love, but others focus on the love of family and the love of God.

And rather than reflect too much on the thrill of love, or the joy or warmth, Atsitty examines the sense of pain, of loss, of suffering, and of longing, that is every bit a part of love as those more positive aspects. She extracts these feelings and reflections out of seemingly ordinary events and rich metaphors, like February snow, eating a cookie, or a hand towel hanging on a nail.

She often evokes scenes from her Diné (Navajo) culture, and this is critical, because ultimately she hopes the reader will feel something of the emotion that she feels and realize that the gap between her native people and Westerners isn’t so large after all. Like the hand and the forearm joined at the wrist, we too are connected.

“I hope I’m able to establish a sense of connection to not only me, but to my people, an understanding and knowing that we’re human,” Atsitty said. “So often people think that we’re different and that we’re not human because we’re so different—because we look different, have a different language, a different humor. Establishing that connection, that ‘this girl knows what grief is and what pain is,’ is very important to me.”

As a father with small children, I found myself connecting to a particular scene in the first sonnet of the book, “A February Snow,” where Atsitty describes a feeling of pain wrapped in a long silent moment:

…It’s tough to tell in this scene if it’s birth or dying time. All I know is it’s the season when wind comes crying, like a baby whose head knocks a pew during the passing of the sacrament, that silence— her long inhale filling with pain.

Perhaps most poignant of all is how Jesus Christ manifests within Atsitty’s work. You’ll find symbolic references within various poems, but it’s also an overarching theme connected to the title: (AT) WRIST.

Roman soldiers pounded nails into Christ’s palms, but the small bones and thin flesh of the palm may not have been enough to support the weight of his body, so many believe the soldiers drove nails into his wrists (or just below the wrist) into a sure place to fasten Christ’s body to the cross.

The wrist, therefore, symbolizes the love of Christ and the pain that is often associated with His love. As Jesus Christ teaches us in the gospel of John, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”

As for references within the poems themselves, “Sonnet for My Wrist” references a hand towel and how “it hangs on a nail above the washbowl, the hand towel, ripped.” And a couple lines down from there, she writes, “When I sleep I keep my palms open.” Finally, near the end of the poem: “I’m born from my father, Tangle People. Our mouths in webs: tonight my wrists part, and you chase my insides until they dangle into pieces.”

“That particular poem introduced the idea of love being painful, and the sacrifice of our Savior Jesus Christ was gut-wrenchingly painful,” Atsitty said. “It presents violent imagery.”

In “Bird Dance” Atsitty calls upon an ancient Diné creation story that tells of the “Monster Slayer” who, for Atsitty and many Christians familiar with the story, represents Christ:

in a virgin creek, leg & thigh of his mother soak up the Sun. Immaculate pulse of radiance & ripple in her soon rounded Middle, jut out for (f)all— Longer than any concentric season, dark and dry Circles reveal a tree split open, what is found between Arm bones—a kind of sheet music with all whole notes, this is how rings sing in the early morn, a choral of cicadas sound come, come as though they had wrists To shake gourds at His coming.

As a doctoral candidate at Florida State University, Atsitty says education is important to spirituality and spirituality is important to all aspects of our lives, including education.

“I can be a better student when I am putting God first,” she said. “When I read and study my scriptures, when I pray, when I put him first at the beginning of my week by partaking of the sacrament, or celebrate Christ at the beginning of each year . . . When I do all these things I find I am a better student.”

Tacey M. Atsitty has presented or read her work at various bookstores across the country, including Midtown Reader Bookstore in Tallahassee, at several universities nationwide, including Brigham Young University, Cornell University, Diné College, and Harvard University.

(AT) WRIST was published on November 14, 2023 and has already received praise from contemporary authors like James Kimbrell, author of Smote; Layli Long Soldier, author of Whereas; and Virgil Suarez, author of The Painted Bunting’s Last Molt and Amerikan Chernobyl. It was also the winner of the Wisconsin Brittingham Prize for Poetry.

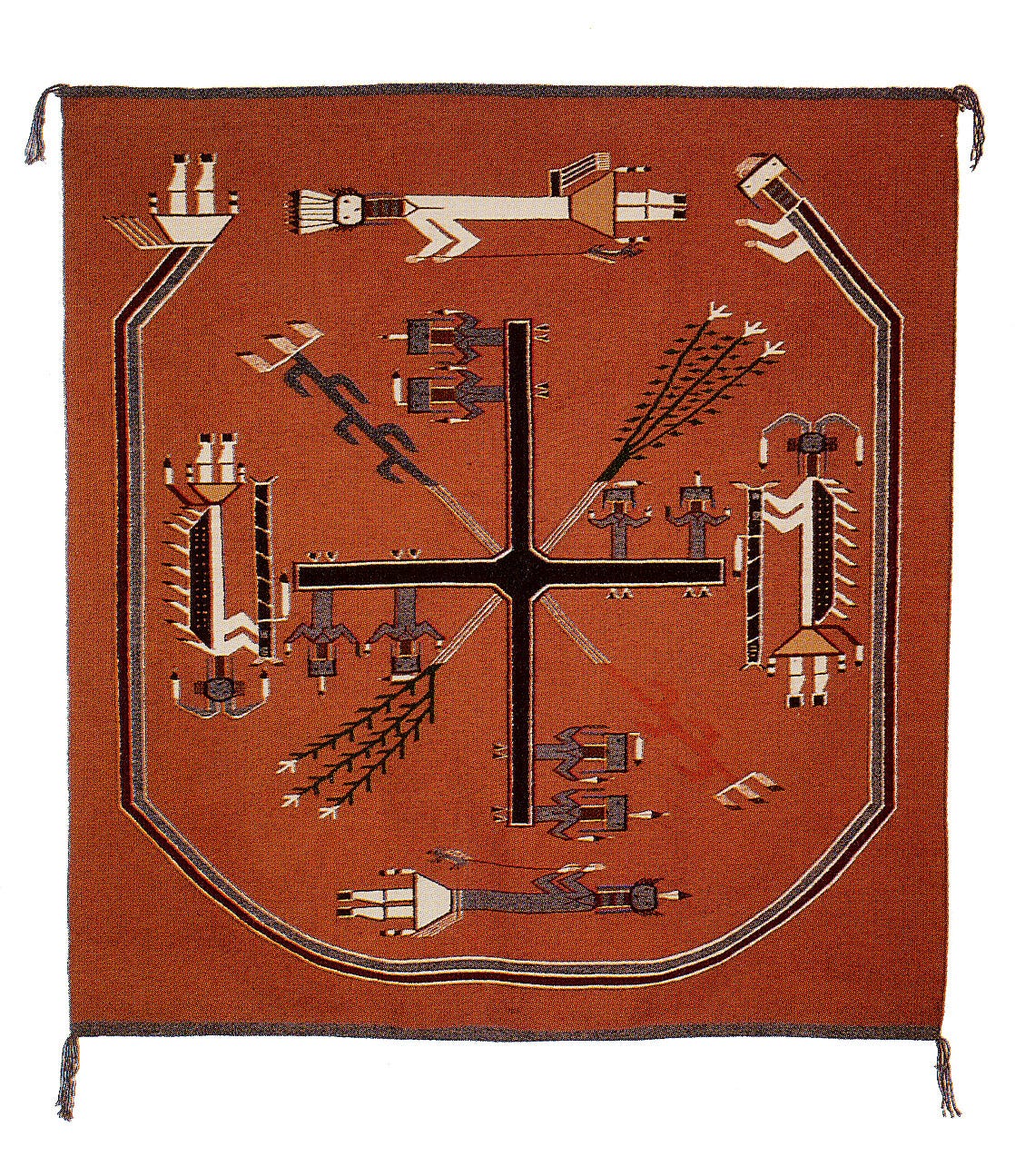

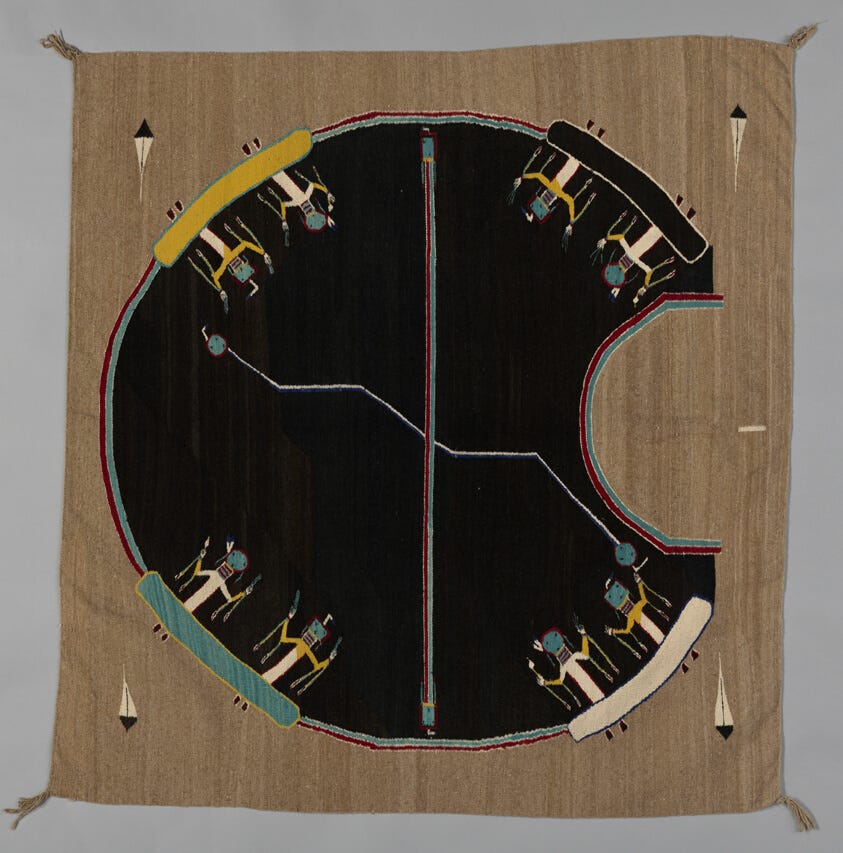

Art by Hosteen Klah.