A Singular, Bright Somebody

This Book Belongs to Afton Wilkinson Hoytsville, Utah Age 14, [Born] June 25, 1923

January 1, 1937

Today I was going to make some Butter Scotch and I didn’t have any Dark Syrup so I didn’t. Today Mother was going to make puffed rice balls and didn’t have any Syrup so She didn’t. My New Years resolution is always do my work with a smile and do it good.

January 3, 1937

Today Betty and I went up to the Bells to see what she got for Christmas she got five Powder Puffs and a case with powder and facial cream, three petticoats and a pair of bloomers. Today Mother made some puffed rice balls and they were a success.

January 6, 1937

Today in Reading I gave my poem “How did you die.” Today the Seventh Grade was examined Doctor French examined me nothing was the matter with me except I was six pounds underweight I weighed 72 lbs and I was 57 inches high.

February 17, 2023 (early afternoon)

I’m staying overnight at the old farm house in Hoytsville for my own writing retreat. I’ve come to this house for 17 years now, having married Afton’s younger brother Cliff’s grandson. This house where Afton grew up is a gathering place for extended family now; my own little family of five often come for the weekend. We’ve spent countless days and nights here: sledding on the snow hill next to the house in the winter, crowding around the fire pit in the back of the house in the summer to roast hot dogs and marshmallows before we head out fishing or backpacking the next day. Often we come for a holiday weekend just to get out of town and feel like we’re stepping back in time, so little has changed.

The farm in Hoystville is no longer inhabited regularly, unless you count the myriad deer, skunks, elk, moose and other creatures that regularly wander around the property, or the mice who’ve taken up residence in several cupboards. Besides the animals, there is a kind of light that settles over the farm, especially on a bright spring day or a long fall afternoon, that burns to a soft glow for hours. It feels like an ancient light that’s somehow found a place to rest for a while.

I found Afton’s diary within three minutes of walking in the door. Like the quiet simplicity outside, it’s easy to spot something new here. Someone found it and placed it on the single dresser in the guest room next to the tote of sheets with the BB gun on top of it. Like the deer, it has suddenly appeared.

I’ve spent the afternoon reading it and typing it up. Hers is a voice I could read all day. I can hear my grandma’s voice in her questions-turned-declarations: Did I have fun. No one speaks like that now. It’s a relic from an era past, precious and fascinating as a phonograph or a telegram.

Afton was born over 100 years ago. That’s over twice my age, a number I can’t comprehend. So much has changed in the world since 1923. Wars, revolutions, technologies that would make the world foreign to her. At the same time, this place, the farm in Hoytsville, aside from indoor plumbing and carpet, has barely changed. I love it for that. The Wilkinson family loves it for that.

There’s a charm that sticks around here. I like small towns. I like their old Main Streets and their quirky businesses and the way people often lean into each other more deeply than they do in a big city. And the cemeteries, with their bright pinwheels spinning next to barely marked graves, make my heart ache just thinking about what a strange circus humanity is, to live and breathe and die in places most of the world has never heard of.

January 9, 1937

Today I stayed in the house and had my head washed, and oh how fluffy.

January 23, 1937

Today Betty came down and we went sleigh riding on the hill by Marie’s house.

April 2, 1937

Today I helped Mother and fed the lambs and horses and helped Dad make a sheep pen.

April 23, 1937

Today we went on our Science trip we went clear up in Wright’s field 8 miles this side of Upton. Were we tired when we got home, I’ll say we were.

May 28, 1937

Today Daddy sold old Spide for 35 dollars he was my favorite horse and a swell pal.

June 25, 1937

Today was my birthday and I had lots of fun too.

July 20, 1937

Today old Bird had a little colt we have called it Peg and is he a beauty he is my pal.

September 12, 1937

Today is Francis Siddoway’s birthday I hope he has a pleasant one

November 24, 1937

Ellen Siddoway came down with Scarlet Fever and so did Francis come down with it.

April 25, 1938

Today in 7th period I was stricken with appendicitis I missed the truck so I went down town and called Aunt Martha.

April 26, 1938

Today I was operated on at 4:00 for acute appendicitis I was not in the least nervous when I got on the operating table.

April 27, 1938

I sure feel awful today. Aunt Martha makes me keep myself covered up so much I nearly suffocate, it’s so I won’t catch cold.

May 6, 1938

I had the clamps taken out of my side today. It sure feels better with them out.

February 17, 2023 (later that afternoon)

I’ve lived along the Wasatch Front almost my entire life. I’m used to small towns with a hick bent, big trucks, red brick Mormon churches on nearly every corner, pastures with horses and cows grazing most months of the year except for the four or so when snow and ice take over everything. It feels good to tuck into a small town, where, if you’re lucky, not much really happens every weekend. Hoytsville is much smaller than where I was raised and where I live now, but is has a kind of quiet grace to it. The farm sits at the end of Creamery Lane, a short road entirely lined with pasture.

What I mean is, this place is as sacred as any. When you come here, you feel in your bones that lives have sprung from this place, worked the land, loved or hated it, wrestled with loneliness and sickness and maybe even what Thoreau called “quiet desperation,” but they’ve been lives with fresh air, a tenderness for animals, a clinging to each other. They’ve been lives with no grand soliloquies or dramatic gestures, just a single sentence about what happened that day. I’ve read enough of my own ancestors’ diaries to know that the simplicity of Afton’s entries isn’t just due to her youth. There’s something in those voices that suggests they don’t have time to sit and write a lot. But there’s also a poetic understanding that words can only capture so much. One’s life is as much a mystery as anything.

Watching the deer for a few minutes, I think how foolish to try to be Somebody.

Or rather, we’re already a singular, bright somebody. Why try to be more?

The mirror in the original farm house bathroom is likely the same one that hung there when Afton was a girl. The glass is warped enough that if you stand just right your face changes and you look like a slightly different version of yourself, your nose slightly longer or your eyes slightly farther apart. Like a twin, with just enough difference to not be you.

My husband’s grandpa Cliff was a twin. Clifton and Clint were the youngest, two cabooses in a train of siblings.

For years I’ve laughed over the family photo on the old TV set of Grandpa Ben and Grandma Gladys, Afton’s parents. He looks stoic, with a very slight smile, a tenderness in his eyes, but she looks unbearably bored, even irritated, that moment right before you roll your eyes. It’s almost a look of disgust. Not necessarily an expression you want memorialized, but there it is.

I’m struck by how little control we really have over our legacy, what signals the stuff of a whole life. A few stories, a few photos, a single diary, a farmhouse that’s loved but old, a farm that isn’t running anymore. I’m sure there’s more, but this is what I can see from the kitchen table tonight.

While I’m here, my mother texts me a few pictures of her older brother when he’s young. She’s just had a large cache of old photos digitized and wants to share what she’s finding.

“There’s something of Coop in these pics,” she says of three photos where an elementary aged boy smiles, his hair slicked back and his ears poking out. Yes, it’s an uncanny resemblance to my youngest son.

She sees my other two boys in herself and her brother as an older teenager. I hadn’t realized how much they looked like my side; so much of them is built like my husband with his long legs and his easy gait, but suddenly the Anderson family is blooming all over their faces. I forget that we can carry such strong resemblances to extended family. We carry pieces of them on our own bodies: a great uncle’s large ears, a grandma’s dimples, a grandpa’s posture. We are all of us a map of familial incarnations. And maybe that’s our deepest legacy: each other.

September 20, 1938

Tonight I went with Lenny Robinson, Betty went with Ellis Childs. Oh boy was them sundaes good.

September 24, 1938

Today I started to menstruate. My tooth is aching and everything else.

November 12, 1938

Today I have brights disease. It sure is miserable. I can’t eat a thing am on a diet of milk.

November 24, 1938

I have been in bed nearly 3 weeks for Thanksgiving they are having mashed potatoes, chicken, dressing, gravy, plum pudding with caramel dip. I can’t have any.

February 18, 2023

I think about how matter-of-factly Afton records deaths. And her own troubles. I can see that there’s a turn at the end of 1937. Sickness enters her world. She seems to record less about daily happenings and more about birthdays and deaths. It’s as if some innocence has been lost between the end of 1937 and the middle of 1938. She seems more aware of her own mortality.

When I was 14, we were two years into a phase of trouble and strangeness as a family. My mother had experienced a severe mental and emotional breakdown when I was 12, and life changed drastically from then on. She left her life as a housewife and went back to college, something I think we all admired at first. But then school became her obsession and we rarely saw her during the week. She was working hard to do well, but it was more than that. As time went on, school wasn’t filling some hole in her, and a kind of restlessness, even agony, took over, and by the time I turned 15 she had become deeply suicidal.

I’m not sure if it happened gradually or in one specific instant that I can’t totally recall, but I remember feeling that though I was still a kid, something in me was also much older, maybe even older before its time. A deep troubling would come over me and I’d have to leave a friend’s house early or go for long walks alone at night to process it. Really, this meant talking to myself and talking to stars and to a God I was just starting to really believe in. And absorbing the world, its vastness and mystery, in the quiet of the night. I felt something wide and deep open up in my universe. While I was still wildly happy at times, even joyous, I marveled at friends whose lives seemed carefree, maybe shallow, whose only worries seemed to be what to wear to the school dance or if some boy liked them. I was suddenly and deeply aware of darkness. The darkness in my mother’s mind that would not leave her. And the reality that tragedy may not be far away. That it lived close. That it could touch me too. Maybe that’s the hallmark of growing up. The realization that you too live in the path of heartache, even death.

December 9, 1938

Today at about 10:00 am I took a convulsion. Oh it was awful. Joe Crittenden nearly got killed in [the] mines.

December 16, 1938

Miss Afton Wilkinson died with brights deases [sic] Dec 14 about 5 o’clock at LDS Hospital in Salt Lake City, Utah. Last she ever wrote by Dawna Wilkinson, Afton’s sister

Written in the July 7 space

Afton I am sick today in body and in my heart. When you went away you took half of my life with you.

Some days you are with me all day other times you are so far away.

I am alone and so very blue. If I didn’t have Dawna I couldn’t go on. Help me give her what she should have to make her a good girl. I wish I didn’t feel like I do about death. It has made me bitter with a little hate in my heart.

It seems like my life has been mostly wrong.

Written in July 9 space

I missed you when school started. There hasn’t been a day that there hasn’t been a terrible cold feeling go over me.

I will always keep your little dresses in the closet I see you when I go there.

February 18, 2023

No one has signed those last two entries. I keep thinking of the woman who looks bored to tears in the photo above the TV. Maybe it isn’t boredom I’m seeing. Maybe it’s a kind of agony that wouldn’t leave her, a grief, a trouble different but similar to what my mother had.

“Bitter with a little hate in my heart.”

I think of the poem she shared in class at the opening of the diary, “How did you die.” What a strange topic for children. I wonder all day what that poem said, where it went.

What is it to lose a child? What is it to grieve? I know a little of this. Our fourth son was stillborn, something that still surprises me to say. It was a full nine months of doctor’s visits, monitoring, worry, preparation. We knew from the blood test early on that he had Down’s Syndrome, but each doctor’s visit brought more bad news. Hole in the heart. Bigger than we thought. Open heart surgery at 2 months. Developing slow. Severely underweight. Then, four days before the C-section, no heartbeat. “He’s gone,” my doctor said to me slowly when, to the nurses and even my husband squeezing my hand, the news was obvious, but I was holding onto the belief they might be wrong.

“This is going to hurt for a long time,” I said to the nurse with the gentle brown eyes. I wasn’t sure if it was a question or an admission to myself or both. She looked at me closely for a moment and then just nodded.

It’s been six years, and still, now and then a wave of grief comes for me out of nowhere and I live in a profound heaviness for a while. Losing a child means you are helpless. It means the center of you is blown apart. And a part of you is unsteady the rest of your life.

Afton wasn’t the first child in her family to die. Her baby sister Deana died at 7 months. I think of her mother, Gladys, and how schooled she already was in grief. And then to lose her oldest daughter just as she was becoming real help and company to her. It’s terrible to lose a small child. It’s a permanent rupture of innocence. But I would imagine losing a daughter at 15 would be equally haunting and would mean the loss of what she was just becoming to you: a female companion in a world of isolation and work. “If I didn’t have Dawna, I couldn’t go on.” Gladys loved her sons, but I can see how she must have needed her daughters. How vital each life is, I think. How much we need each other.

Bright’s Disease isn’t a term we use anymore. Now we call it “acute or chronic nephritis” or kidney failure. It strikes me as significant that Afton experiences kidney issues eight months after her appendix bursts. Especially since one of her earliest entries says that Dr. French examined her in a routine checkup and “nothing was the matter with me except I was six pounds underweight.”

I marvel all weekend at this little diary. One of my husband’s aunts or uncles likely found it the day we deep-cleaned the farm, though no one spoke of it that day. Originally meant as a “Five Year Diary” and labeled as such on the front of the soft leather cover (complete with a strap and lock), Afton only used two of the years. But in those years there’s a striking arc that moves from childhood into maturity, as if, between the lines of each entry, the world and the realization of her own mortality bloom, until that dark flower takes over everything.

Truthfully, I never even knew about Afton. Maybe someone mentioned before that Grandpa Cliff had a sister who died young, but I only remember hearing about Dawna, her photo in the front room, hair golden and curled, posed like an old-time movie star. Only the diary witnesses of Afton. She’s a ghost, nothing to witness of her but her own voice. But it’s a voice of brightness and love, of a fierce tenderness for the world around her. All weekend I am haunted by this voice and the realization, again, that even the smallest voices, even the faintest or briefest, are beautiful. That we are more than a human race, we are a family of eternal beings whose voices teach and celebrate and mourn and witness. Voices that remind us, I grieved, I loved, I meant something to the earth.

My husband texts me a photo of Afton at 14 that he found online in Family Search. It’s blurry, but her face is open and sweet. The outside of her eyes slope down slightly, making her look the tiniest bit sad, though she’s smiling. Her mouth is closed but turned upwards, a teenage smile, a little reluctant but still childlike. There’s a bow in her hair. Her body is turned sideways but she’s facing the camera, as if she just turned for a moment to look them in the eye then move on. The blurriness too says she’s caught in action. A quick capturing. A literal snapshot. A life.

Sunni Brown Wilkinson is a poet and essayist. She is the author of three poetry collections: Rodeo (winner of the 2024 Donald Justice Poetry Award and forthcoming from Autumn House Press), The Ache and the Wing (winner of the Sundress Chapbook Contest), and The Marriage of the Moon and the Field. Her work has been awarded the Joy Harjo Prize, the New Ohio Review NORward prize, and the Sherwin Howard Award. She holds an MFA from Eastern Washington University, teaches at Weber State University, and lives in Northern Utah with her family. Find her at sunnibrownwilkinson.com

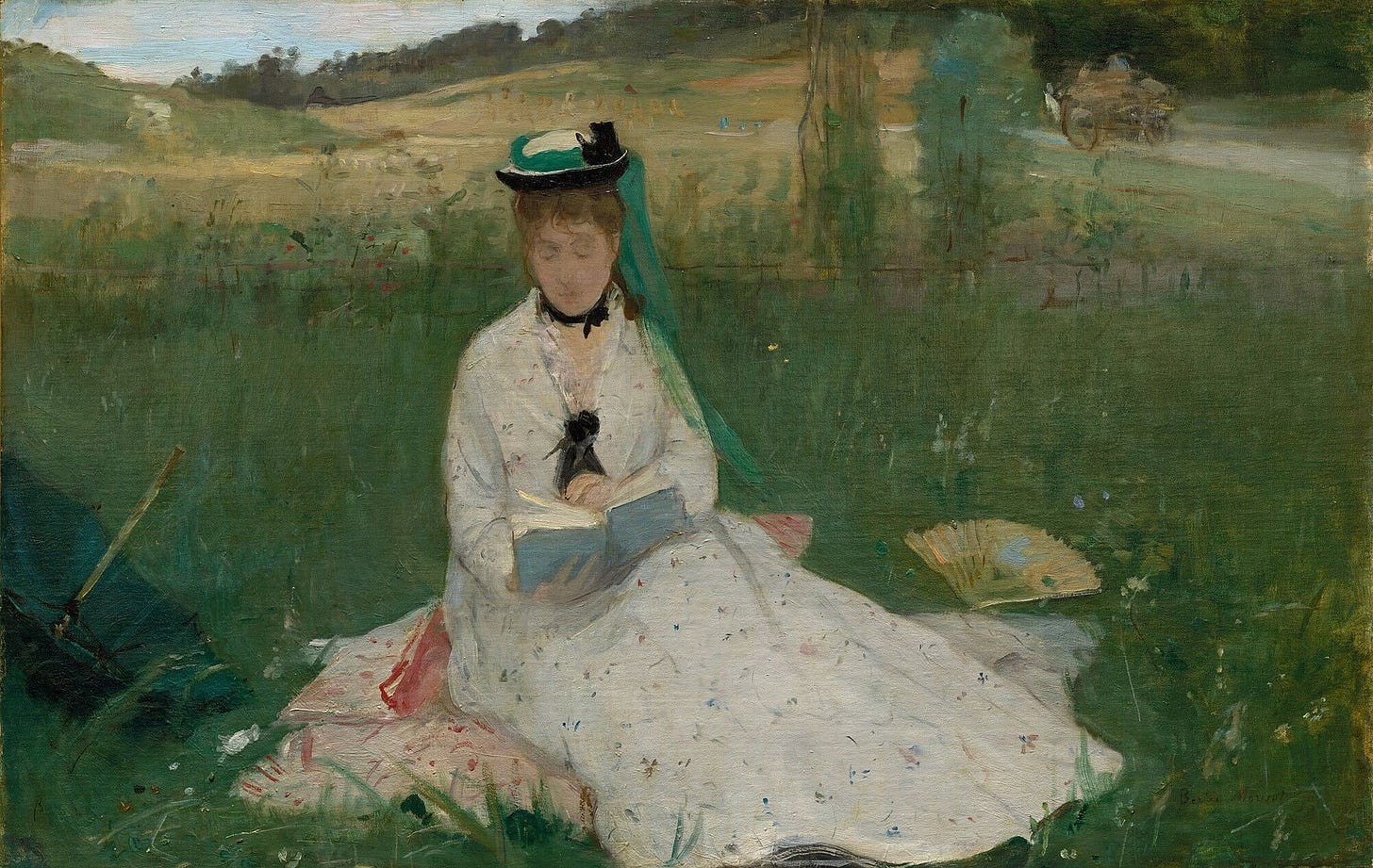

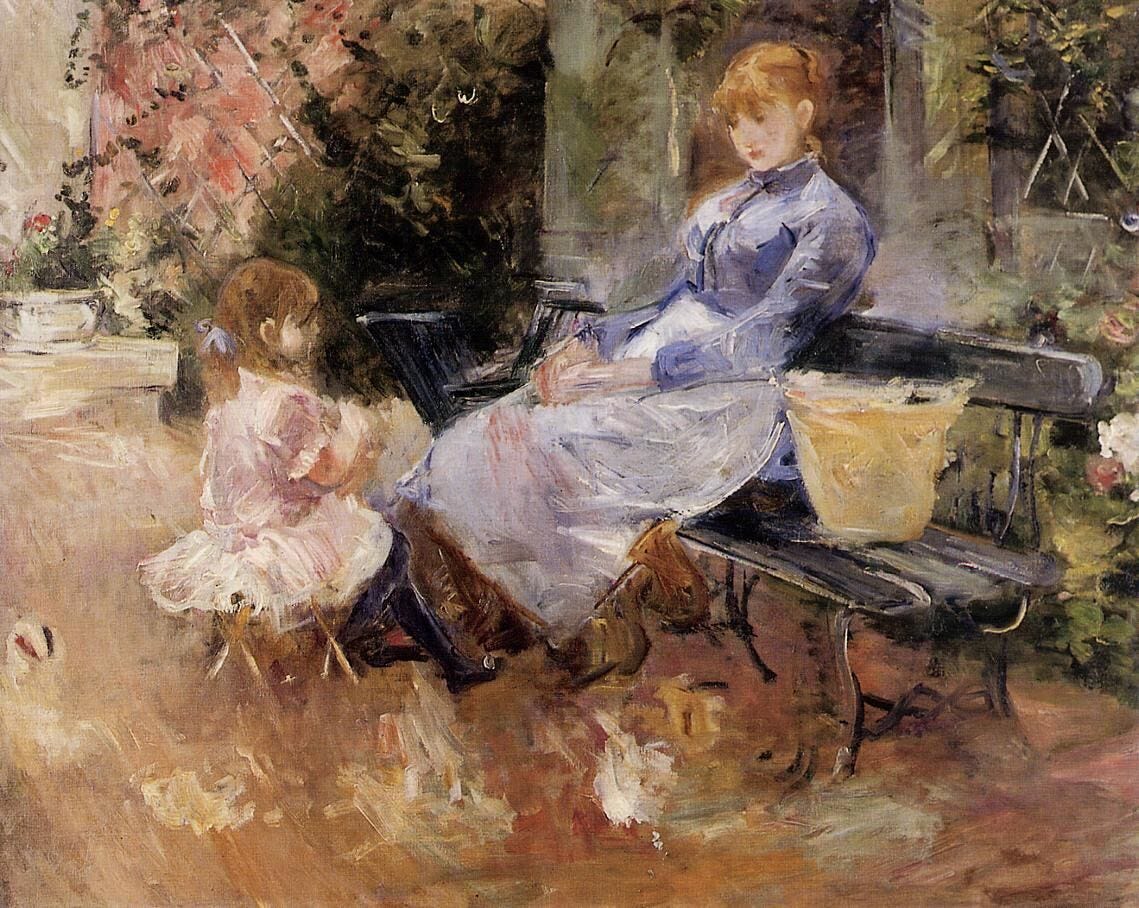

Art by Berthe Morisot.