Second Nephi, alone among all books of the Book of Mormon, is divided by its author into two parts. What event constituted such rupture that Nephi felt a need to recommence his history from a new starting point? Perhaps surprisingly, it was neither the death of the patriarch Lehi nor their arrival in the Land of Promise. The destruction of Jerusalem and its holy temple signaled the dramatic break with the past—with the homeland and, his people feared, with the covenantal promises.

A future without Jerusalem and her temple may well have been inconceivable to the small band of Israelites headed into the unknown, already riven by doubts, rebellion, and factionalism. For Israel, this most traumatic event in their history was the crisis that incentivized their first canon—the Torah—and a rethinking of their identity as a people of the covenant. So, too, with the people of Nephi. As Moroni expressed Nephi’s task, he had to bear record of “the remnant of the House of Israel” and assure posterity that “they are not cast off forever.” This entailed making one theme prominent above all others, in their understanding of covenant: “Jesus is the Christ.”

Covenant Theology

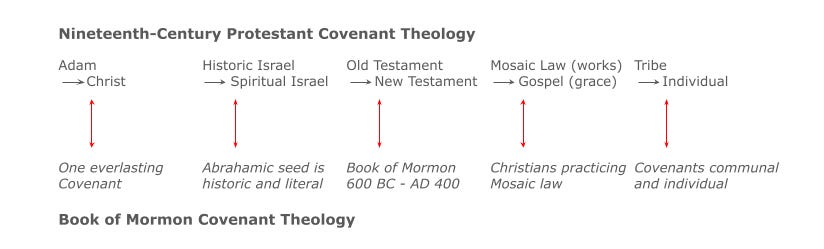

Modern readers are generally familiar with the centrality of covenantal thought in Jewish history and scripture. Less well known is the fact that Christianity—especially in the era of the Book of Mormon’s appearing—was similarly oriented around covenant theology. The basic principle Christians taught emphasized the radical contrast between the covenant associated with the Old Testament (the gospel of works) and the covenant associated with the New (the covenant of grace). The first was understood to be the covenant made with Adam—and renewed with Noah, Abraham, and Moses—that emphasized obedience to the law. The second was thought to describe a new covenant that emphasized salvation by means of faith in Christ’s atonement. The Old and New Testaments have been taken to represent these two distinct versions of God’s covenants with humanity. Parting from this dichotomy, the Book of Mormon, beginning most emphatically with 2 Nephi, collapses these polarities into one, effectively synthesizing the old and new covenants into one everlasting covenant (hinting toward the eternal new and everlasting covenant that comprises the gospel plan laid out before the foundations of the world). And so we can see that the binaries shown in figure 1 below effectively come together.

One by one, the Book of Mormon dismantles these oppositions and integrates them. Adam and Eve did not precipitate a catastrophe needing correction, but furthered the execution of an original gospel covenant. The covenant did not pass from historic Israel to a figurative, Christian Israel, but as Nephi read Isaiah, would assimilate both. The Book of Mormon itself spans Old and New testamental periods. The atonement of Christ did not signal a rupture with the Mosaic Law as it launched a new covenant, but rather unified Mosaic law as preparatory and gospel law as eternal—both centered in Christ and both practiced by ancient Nephites simultaneously. Finally, we find in the Book of Mormon that covenants have both a communal and an individual dimension.

Lands of Promise and People of Promise

Reading 2 Nephi, one cannot help but note the highly pertinent lessons that it had for the first generation of Saints who read it. Saints pursued more than one place of gathering, believing that the inheritance of a literal Zion was within their grasp—only to be disappointed in their desires.

It is no coincidence that Nephi, faithfully, and Laman, Lemuel, and Sariah, complainingly, all count the cost of leaving behind as “the land of their inheritance.” After the trauma of exile and loss and resettlement in a new “land of promise,” or a new land of “inheritance,” they suddenly become exiles again in 2 Nephi, fleeing from their rightful inheritance. It is after this second exile from what they had thought to be their new land of inheritance that Nephi directs the building of a temple in what is now their third land of settlement. Does the building of the temple suggest something significant about how a land of promise becomes marked as such? In any case, it would seem that with prophetic leadership, a new place of refuge, and now a temple, the Nephites’ shadow of the original land of promise in Jerusalem has at this stage become its effectual replacement. And yet, this third site, settled as a land of promise, proves to be as unstable as the past versions. In the first generation of the Restoration, the Saints also learned by costly experience that covenant peoples are made by keeping temple commitments, not by inheriting promised land. As a covenant-oriented people, we can profit from the moral that 2 Nephi unfolds to us.

Christ the Healer

And these covenants, now as then, must be rooted in personal experience of the Christ who stands surety behind them. Here, however, we encounter first-hand testimonials that the Christ of scripture is a living God, manifesting himself to flesh and blood individuals, reshaping our own reality as one still pregnant with the possibility of our first-hand communion with the divine. These multiple first-person accounts shatter the historical uniqueness, and remoteness, of the Jesus depicted in the New Testament. Into this immense historical vacuum strewn only with dusty fragments and well-worn stony paths, the Book of Mormon bursts with a remarkable, audacious claim: Jesus was not a once-in-eternity incarnation of the Divine, flashing like a shooting star into the long night of history. His Palestinian birth and ministry were not the beginning and end of his human interaction, and the Old World and its people are not the only setting in which he loved and healed. The Book of Mormon multiplies the field of Christ’s operations and its perseverance across place and time.

The study of 2 Nephi is also remarkable for the “plain and precious truths” of which it testifies, often obscured in the contemporary religious landscape. Foremost in this regard, and turning almost two millennia of Christian understanding on its head, Lehi pronounces the absolute necessity behind our first parents’ decision in the garden:

“And now, behold, if Adam had not transgressed he would not have fallen, but he would have remained in the garden of Eden. And all things which were created must have remained in the same state in which they were after they were created; . . . and they would have had no children; wherefore they would have remained in a state of innocence, having no joy, for they knew no misery; doing no good, for they knew no sin” (2 Ne. 2:22–29).

Nephi is the first in the Book of Mormon to employ the term atonement, and he will use it more than any other writer until we get to Alma. It is entirely fitting that in the very first chapter of this book of 2 Nephi, as Lehi bids farewell to his posterity, he bears witness to the fruits of the oneing that he himself has personally experienced: “I have beheld his glory, and I am encircled about continually in the arms of his love” (2 Ne. 1:15). To personal witness is added the most scriptural light on the atonement that we have—incorporating principles of human agency, tender mercy, and Christ’s sharing of “the pains of all [humans].” Finally, in Nephi’s concluding testimony, he poignantly calls us to the greatest of human tasks: to direct others, by word or deed, to Christ the Healer.

Terryl Givens is a Senior Research Fellow at the Neal A. Maxwell Institute at BYU. His books include studies in theology, biography and intellectual history. To receive each new Terryl Givens column by email, click here and select "Wrestling with Angels."

Artwork by Brian Kershisnik.

This essay appears in Theological Insights from the Book of Mormon, a Wayfare series that pairs the 2024 Come, Follow Me curriculum with authors of the Maxwell Institute’s Brief Theological Introductions to the Book of Mormon series.

Other articles in this series:

UPCOMING EVENT

NEWS

The B.H. Roberts Foundation recently distributed 80,000 postcards to a random sampling of households throughout the “Mormon Corridor”, collecting survey information on 2,625 members and 1,183 former members on a number of questions related to beliefs, practices, and experiences within the Latter-day Saint tradition. You can read more about this survey in this Deseret News piece or check out the study’s methodology here.

Co-sponsored by Wesley Theological Seminary and the Wheatley Institute at Brigham Young University, the Washington National Cathedral will be holding a special public forum, “With Malice Toward None, With Charity for All”, on February 21st at 7:30 pm. Forum guests include Republican Gov. Spencer Cox (Utah), Democratic Gov. Wes Moore (Maryland), as well as other scholars, journalists, legal experts, and public thinkers.

JustServe, a humanitarian outreach organization sponsored by the LDS Church, recently announced future collaborative efforts with the most famous YouTuber, MrBeast. Drawing on his extensive global reach, MrBeast announced “We’ve recently partnered with JustServe, an app that helps match volunteers with the right organization. By registering all of your interests, and when you can be available, the app will then offer a list of opportunities to best serve you.” More information about the partnership can be found here.

The Sunstone Education Foundation has resurrected an early publication from its past, The Sunstone Review, though this time with a “21st century face lift.” Offered as a collection of “snack size articles about Mormon culture, history, thought, and experience, curated to fit even the shortest 2024 attention span,” this feature is free and available to read online.

Wayfare regretfully shares notice of a recent tragedy which has befallen Exponent II, in which a number of their Fall 2023 issues were suspiciously lost or damaged in transit. If you have been personally impacted by this unfortunate situation, you can receive your issue by filling out the following form. Additionally, any support towards Exponent II in the form of new subscriptions or donations would be surely appreciated at this time.

Very insightful. This is all elaborated upon in Brother Givens' contribution to the Maxwell Institute's wonderful "Brief Theological Introduction" series, for which he authored the book on 2 Nephi. Highly recommended!

Enjoyed this analysis. Kristor Standahl said the B. of M. was most striking as a pre-Christian Christology, but it was also a blending of Hebrew group salvation and Christian personal salvation--as you note. It is a book for our day too because it raises the global or cosmic question of God's 'field of interest.' The underlying soteriological and epistemological question for Nephi expanded from 'why me', to 'why us' to the tension between 'why not everyone' and 'what if everyone': Why does the 'Parental' God of all humanity pick and choose among his children to reveal truth so sporadically and differently. I Nephi 17 is Nephi's classic theodicy: 'well, the Canaanites had to be bad guys for God to kill them, right?' Answer: He cares for all of his children but the righteous are favored. But how can people be righteous if they don't have the gospel? 'There are only two churches' helps ease this aporia reducing the human test that matters to Matthew 25 (when did we know Thee?)--following the universally given Spirit of Christ (Lamb of God 'church' members) which leads to serving the needy, and following the dark spirit (G&A 'church' members) which leads to harming by neglecting others. Still there is no discussion of pre-mortality or the spirit world where 'fairness' is assured. Still a sovereign all powerful, fore-knowing God seems to be getting his way and helping some more than others from the outset . . . hmm. Later (2 Ne 29, Alma 29, 3 Ne 15) this subject is expanded well beyond Israel. we are told there are indeed 'other sheep' and 'still other sheep' but where they are is left unclear. They might be the guys sitting next to us a McDonalds or on countless worlds coming and going . . . the yearning of the faithful to make God seem fair goes on. A know-all God is usually the weak reading for this. I prefer Gods who are leaders doing their best most of the time--living with aporia in eternity.