A History of Trust in God

An Interview with Teresa Morgan

Teresa Morgan is the McDonald Agape Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at Yale Divinity School. In this interview, Morgan and Wayfare Editor Zachary Davis discussed how ideas of faith and trust have evolved in Christianity.

This interview appears in Wayfare Issue 7. To receive a print copy of the magazine, become a paid subscriber or Faith Matters donor by March 31.

You have made a deep study of the history of the word faith. Tell us about the original meaning of this concept as understood by New Testament Christians.

Nowadays, when we talk about Christian faith, we think about things that we believe. Early Christians believed things, but for them, belief was the basis for trust. Belief was the foundation, but trust got you into the community of the saved and kept you there. Greek pistis and Latin fides are the terms that we translate as “faith” or “belief.” In the Greek and the Latin of their day, these terms meant trust, faithfulness, trustworthiness, or good faith. For very early Christians, pistis language centrally meant trust. It meant trust in God, trust in Christ, faithfulness to God in Christ. It meant the trust that God and Christ put in us. All the other things that we associate with faith now are evolutions out of that.

How were pistis and fides used before Christianity?

They were everywhere in society. They were used for the trust between family members, which was very positively viewed in the ancient world. They were also used for trust between friends. In the world of the first century, where Christianity developed, trust between friends was regarded as highly desirable but quite difficult. The terms were also used in commercial contexts for making contracts and covenants, and in political contexts, of course—there was a lot of worry in the world of the first century about the trustworthiness of rulers, especially emperors. Emperors were generally regarded as not very trustworthy.

There was also a lot of interesting discussion about whether you could trust the gods. The world into which Christianity was born was a world, as far as we can tell, with very few atheists. We hear almost nothing about atheism. Almost everybody just took for granted that the gods existed—the gods of Olympus, all the gods of the ancient world—but there was a lot of debate about whether you could trust them. They were often not trustworthy, and that’s one of the big differences between mainstream polytheism and Judaism and Christianity: for Jews and Christians, God is absolutely trustworthy, and that’s a huge new thing in that world.

People didn’t see Zeus and the other pantheon gods as family members, but Christians did start to think of the Christian God as a loving father and see themselves as children of God. Is that right?

Yeah, Greeks and Romans could refer to Father Zeus or Father Jupiter, but it wasn’t incredibly common and it doesn’t seem to mean the same thing to Greeks or Romans as God the Father came to mean to Christians. It was a more distant, authoritarian relationship, one of regulation and punishment rather than of love. The use of loving family language among Christians and Jews was very distinctive, and the language of God as father was significantly more common among Christians, even than Jews.

One of the reasons trust was such a strong theme for Christians is that they thought in these family terms. They were very unusual in calling other members of the community “brother” and “sister,” so that family language really goes alongside the language of trust.

When did belief or cognitive assent to concepts begin to take primary meaning of the word “faith?”

It happened somewhere between the end of the first century and the Council of Nicaea in 325. We can give a definite date for the moment when belief became officially central to Christianity because the creed that was developed at the Council of Nicaea was the first ever instrument created by Christians that the whole of the church was supposed to sign up to. It was created to test whether somebody was a legitimate member of the church based on what they believed—to test for heresy. The Nicene Creed was not used liturgically for over a hundred years. That’s not what it was for. It was a test of orthodoxy, and that was the first moment when really believing defined you officially as a Christian.

The path to that creed had to do with the fact that Christians found themselves being attacked by outsiders. Through the second and third centuries, Christians spent a lot of energy defending themselves against outsiders who thought their ideas were ridiculous or vulgar or immoral. So early Christian apologists spent a lot of time saying, “Actually, what we think about God and Christ is not irrational or ridiculous or just stupid or ignorant. It’s true, it’s carefully thought out, it’s sophisticated. It makes sense, it holds together. It’s reasonable.” And by defending Christianity as reasonable, Christians came to talk a lot more about belief.

Christians also had a lot of debates among themselves about the nature of God, the nature of Christ, and whether Christ is entirely human or entirely divine, or something of both. And if something of both, in what way? Belief language became more important in these debates.

Another part of this is a sort of accident. Platonist philosophers used pistis language in a very particular way to refer to beliefs that we can draw from this world about the gods. Most people used pistis to mean trust. And it just so happened that some of the most influential early Christian theologians were Platonists, and they adopted this platonist use of pistis, meaning belief rather than meaning trust.

So all those things together gradually encouraged Christians to think about their faith more in terms of belief, and the seal was really set on that at the Council of Nicaea. And since then, belief has been really central to Christians.

What do you think is lost when we lose this original sense of pistis?

I think we lose that sense of relationship with God, that it’s our family relationship with God and with Christ that is central to our faith. And that’s a relationship that we give the whole of ourselves to. It’s not just a mental or cognitive thing. It’s about your heart and your soul and your strength as well as your mind.

When you focus on belief, it can be easy to think it’s about what you think—thinking the right thing. What is interesting about Christianity is that if you ask the average Christian who goes to church on a Sunday, I think they have always said, and do still say, trust is very important. Faithfulness is important. They do actually think in terms of relationship, in terms of entrustedness and trustworthiness. It’s the theologians who’ve forgotten about trust and have got a bit hung up on the belief thing.

This word “entrustedness” is unique and beautiful. Tell me how you think about entrustedness.

There’s actually quite a bit of language of entrustedness in the New Testament, which we don’t really take very much notice of.

Think about the parable of the talents, where the master goes away and before he does, he gives three of his trusted stewards talents. One gets five talents and ends up with ten, and one gets two talents and ends up with four, and one gets one and buries it. The two good servants who multiply their talents are described as pistos—trustworthy. The one who buries his talent is not trustworthy and he’s cast out. So the language of being entrusted with something goes very well with the language of stewardship.

We find it too in the epistles. Paul, in 1 Thessalonians, describes himself as entrusted by God with preaching the gospel. In 2 Timothy, we hear the writer tell his audience to “guard this rich trust that you have been given”—which is the teaching of the gospel, so it’s something they have been entrusted with. So in New Testament writings, people are entrusted with different things—with preaching, with healing. It’s language that parallels the language of gifts of the Spirit.

So we are taught that we can trust fully in God, and we strive to live worthy of the trust that God places in us.

Yeah. Part of the theological logic of this language is that God trusts us. God is often said to be “faithful” in the Septuagint and several times in the New Testament. And part of God’s faithfulness to us is that God trusts us. God trusts us, for instance, by sending Jesus into the world to build a bridge between God and an alienated humanity. God trusts us to recognize Jesus—to recognize God with us in Jesus Christ, which is a big act of trust when you think about it.

God could have done what the prophet Zachariah prophesied and stood on the Mount of Olives in a blaze of glory and said, “Okay, this is the deal.” But God doesn’t do that. He sends Jesus Christ, a human being, to Nazareth to preach and heal, and he hopes that people get that this is the Son of God.

It’s a fascinating model. It is a great act of trust by God, and Jesus similarly has to trust that people will hear him. So there’s trust from God’s side as well as from ours in this relationship, which is what you would hope for and expect in a family kind of relationship. It makes sense in a family context. All members of a family trust each other, and that’s very much the Christian model.

You’ve taught at some of the great universities in the Western world. Faith, or at least belief, has been embattled in the West. What counsel do you have to live faithfully with both heart and mind?

It’s a question my students ask on a regular basis. For myself, I have never felt it to be a problem because I’ve been very fortunate that my whole life I’ve had such an overwhelming sense of the presence of God. It seems to me that to open your eyes, look at the world, and listen to the world around you speaks of a universe full of the divine, and it always has. All my intellectual exploring is just excited, joyful, and fascinated ways of trying to understand God better.

Now, that’s kind of easy if you always have a strong sense of God. But I have many friends and many students who struggle with that sense, and it is well documented that a great many saints, theologians, and people of great faith do often struggle with the dark night of the soul—the sense of the absence of God or not hearing God. I can see that you might worry that your thinking might lead you astray.

I suppose either we hang on to our own sense of the divine, or we hang on to our corporate sense of the divine. One of the incredibly important things about Christian tradition and Christian community is that we hold our faith for each other, and on the days when we wobble or we can’t hear or feel God, then we know that there are people around us who do still hear and feel and see the presence of God. And we hold that faith for each other—we hold that trust for each other. People through 2,000 years of Christian history have held it for us and handed it down to us.

I say to students occasionally: You’re not going to break God. Explore. Everything that we do is just exploring the wonder of what God has given to us. But if there are days when you can’t feel that, then put your trust in the people around you and the tradition, which feels that for you, and hang on to that. Hang on to what we are taught, what we see the people around us doing, until perhaps you get your direct sense of the presence of God back again. But for those of us who believe in God, who trust in God, we’re not going to break God. All our exploring is just dancing on the breath of God.

Teresa Morgan is the McDonald Agape Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at Yale Divinity School.

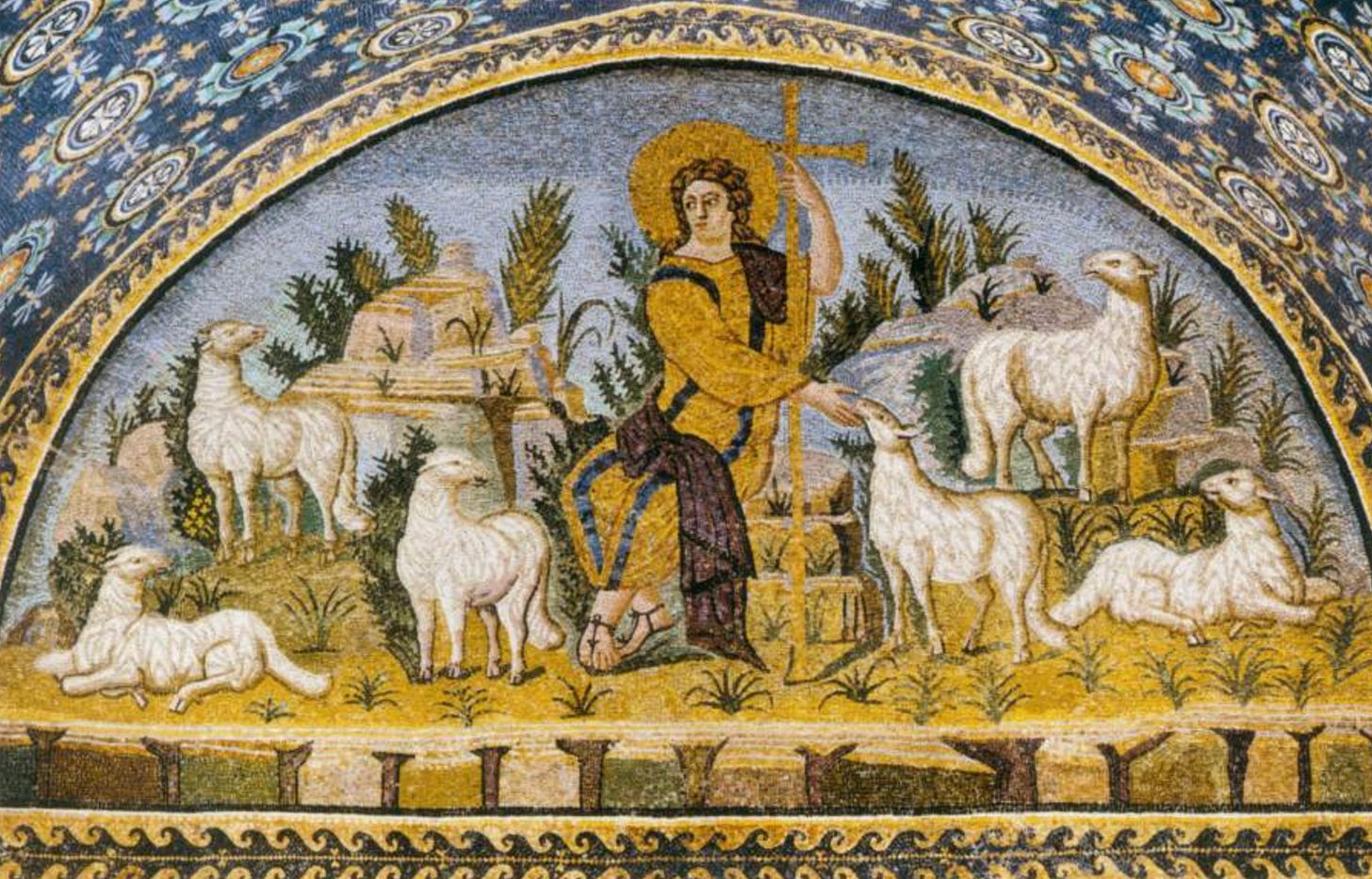

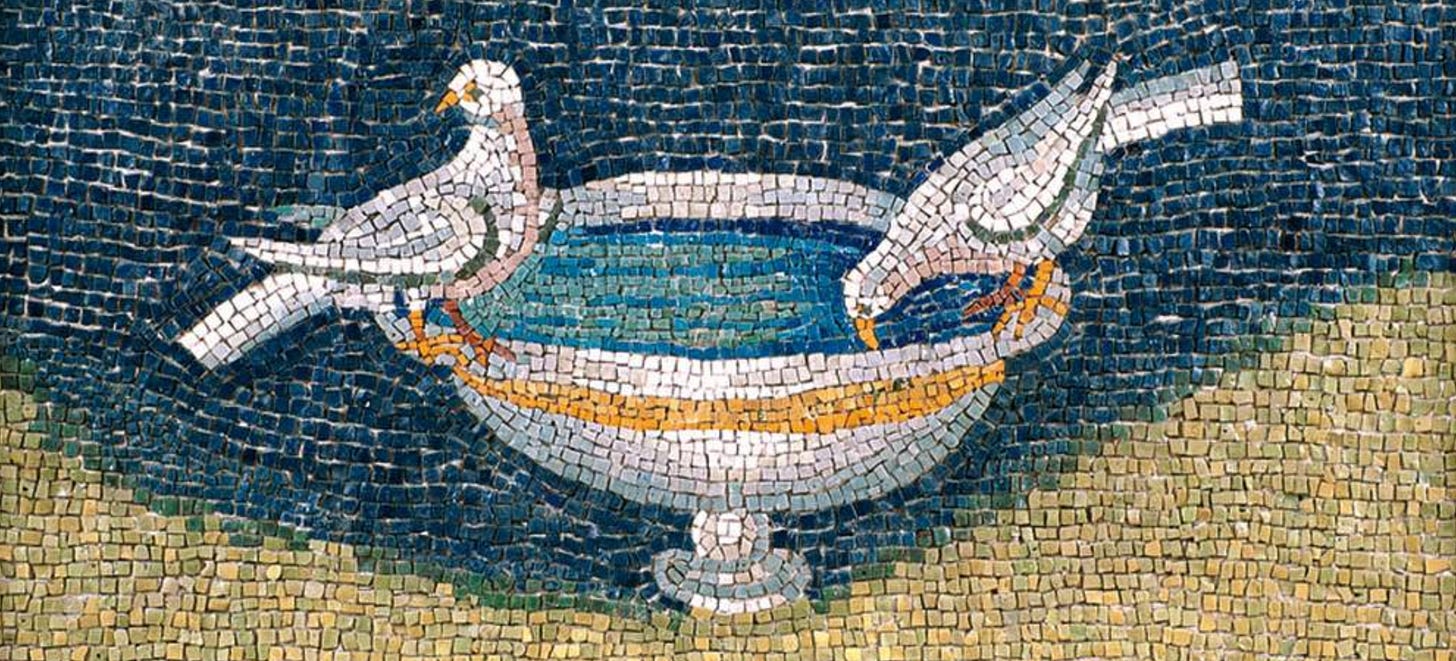

Art from Mausoleum Galla Placidia.