This essay is an excerpt from Jonathan Stapley’s important new book, Holiness to the Lord, published recently by Oxford University Press.

One day, in the year before I was born, my dad received a call at work. He was a lay church leader at the time, and our ward included some forest land next to a city park. Those calling him asked that he meet them at this property, and when he arrived, they began to count trees. It was the site for a temple in Bellevue, Washington, that now serves the Seattle area.

Before the Seattle Temple was dedicated, there was an open house. Hundreds of thousands of community members walked through it, including the governor and federal officials. Newspapers throughout the Pacific Northwest carried articles about the temple and its fixtures, with pictures of the baptistry and “celestial room.” They wrote about the color of the carpets, the “Czechoslovakian crystal chandeliers,” and “French provincial furniture.”

After the open house, Spencer Kimball, who led the church as its president, dedicated the temple, and then closed its doors. From that moment, local church leaders have worked to find every opportunity possible to open them for their faithful members. But no non-members have entered since that time.

It has always been easier for Latter-day Saints and their leaders to talk about the construction materials and furnishings of the temples than what actually happens inside of them. The way the Saints have guarded their speech about the temple over nearly two hundred years is complicated. The temple is sacred and holy, but it is also separate. It is true that participants in the temple commit to never disclose certain aspects of the ceremonies outside of the temple, but those aspects are an extremely limited proportion of the overall experience. Nevertheless, Latter-day Saints have viewed most or all of their experiences in temples as private. Culturally, the temple is found in this space—beyond public access.

However, in recent decades, church members and church leaders have had to negotiate the privacy of the temple experience with the heightened visibility of temples because of the increasing numbers of temples as well as the public nature of our most important medium of communication—the internet. Church leaders appear to have decided that it is time to disclose to the public not only what temples are made of, but what they are made for.

Joseph Smith revealed an expansive cosmology, where “kinship, priesthood, government, and heaven all became synonymous.” In this new understanding, heaven was not a reward or destination. It was relational—a network of people materialized through the rituals of the temple, a “cosmological priesthood.” Throughout the nearly two hundred years since Smith introduced it, the temple has remained a liturgical space where Latter-day Saints generate a sacred, cosmic identity. The temple is a site where Latter-day Saints order their bodies, their communities, and their universe. Moreover, this work has not been static; this identity generation is the product of continual adaptation in response to cultural change.

The privacy of the Latter-day saint experience in the temple is still important. Under the protection of this privacy, many Latter-day Saints have received meaningful mystical experiences. As scholar Hugh Urban has noted, these experiences are generally personal and largely incommunicable. However, the visible liturgy of the temple has done important work not only to shape the lives and minds of its patrons, but to create new relationships.

Throughout his ministry, Joseph Smith repeatedly identified biblical archetypes which he ritualized. The culmination of this process was his expansion of John of Patmos’s apocalyptic vision. In describing his theophany, John quoted a heavenly hymn to Jesus, who “redeemed us to God by thy blood out of every kindred, and tongue, and people, and nation; And hast made us unto our God kings and priests: and we shall reign on the earth” (Rev. 5:9–10). This was temple imagery from the Hebrew bible appropriated and recast to describe the Christian heaven. Through Joseph Smith, this vision of heaven became the concrete product of the Latter-day Saint temple liturgy. The temple created a kingdom of priests and priestesses in heaven and on earth—performed biblicism on a cosmic scale.

For Smith, this heavenly concourse necessarily incorporated men and women. In the temple liturgy, women dressed in the clothing of the ancient Israelite temple priests, just as men did. Then through relational sealing rituals Latter-day Saints fixed their family relationships for all eternity. They planned on extending those relationships through the entire history of humanity. They constructed the eternal past, present, and future in a timeless network of relationality. For Latter-day Saints, identity as eternal kin is inherent to the identity as members of the heavenly priesthood.

The Latter-day Saint experience with the temple has shifted in important ways since a mob murdered Joseph Smith in 1844. Still, this vision of kings and queens, priests and priestesses, remains imprinted on the temple liturgy and its material culture to the present. The temple has functioned as a dynamic map that orients church members as they move through space and time. This movement necessarily requires change in the individual, but also in the community more broadly and in the temple itself. For example, the way temple access has regulated Latter-day Saint food practices and sexuality has differed dramatically across generations. The possible family relations created through temple ritual have similarly varied. Building from the procession of twentieth-century sociologists of religion, Armand Mauss argued that Mormonism’s historical persistence is the result of a balanced tension of change—retrenchment to insider peculiarity on one hand and accommodation with the broader culture on the other. The temple remains a central liturgical site for Latter-day Saint identity formation. It has also been a central location for this balanced adaptation in the face of cultural change.

I imagine that most people in Bellevue, Washington, have never noticed that the streetlights on the freeway overpass below the Latter-day Saint temple are painted with red and white horizontal stripes. The careful observer will also see that there are inactive strobe lights that cap these tall structures. When the Seattle Temple was first dedicated it had a shorter spire than it does today, and the West-facing Moroni at its top had a base with a red flashing light.

These were concessions planners made to get a temple built so close to the nearby municipal airport. It has been about forty years since this airport was closed and demolished. Office buildings and hotels now stand where aircraft taxied, took off, and landed. These striped streetlights are one of the few things that remain.

There are aspects of the Latter-day Saint temple and its practice that are like the freeway overpass beneath the Seattle temple. In many cases, structure–function relationships are observable and evident. There are also elements like those red and white streetlights—facets of belief, practice, or material culture where function is not immediately clear. It is with this earthly history that Latter-day Saints do heavenly work, the work of the temple liturgy—the Latter-day Saint construction of a kingdom of priests and priestesses in heaven and on earth.

Jonathan Stapley is an award winning historian and scientist. Oxford University Press recently published his volumes, The Power of Godliness and Holiness to the Lord: Latter-day Saint Temple Worship, from which this essay was adapted.

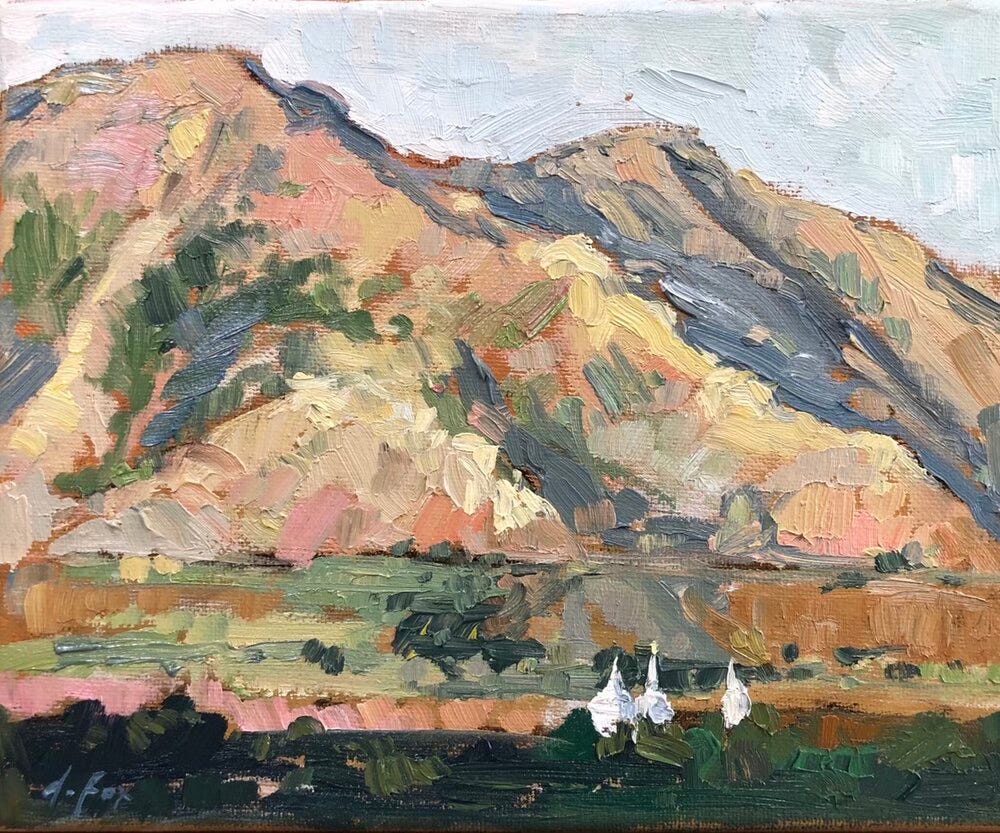

Art: Manhattan, Brigham City, and Boston by Deb Fox.