In 1925, the Church formally took root in Latin America when it opened a South American mission in Buenos Aires, Argentina. To celebrate the hundred-year anniversary of this monumental event and its expansive spiritual and cultural implications around the world, we offer a special series of essays by Latin-American authors.

—Tricia Cope

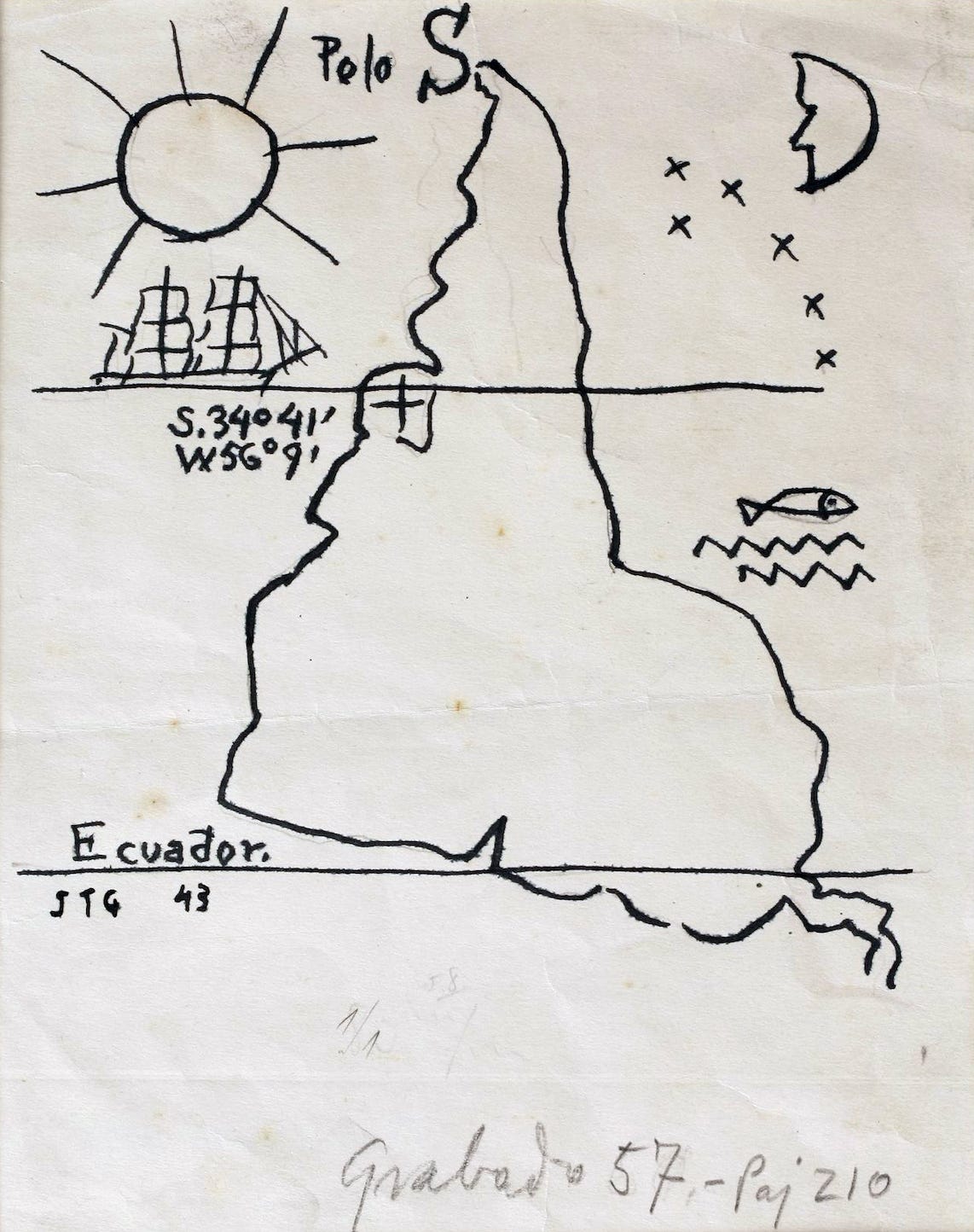

In 1935, Uruguayan artist and educator Joaquín Torres-García established his Escuela del Sur (School of the South), declaring “Nuestro norte es el sur,” or “Our north is the south.” It was a playful statement with a provocative meaning. For generations, the leaders of South American societies had looked to Europe, and sometimes the United States, as intellectual, cultural, and aesthetic models. Most world maps put Europe at the center, with South America tucked away into an often-overlooked corner. Even compasses were built to identify north and define the other directions relative to it. But things didn’t have to be that way. A compass could just as easily be designed to point south. A map would be just as accurate upside-down and with South America placed top-center. What would happen if South American artists and thinkers learned to do the same kind of reimagining, treating their own physical and cultural world as a baseline?

By saying, “Our north is the south,” Torres-García was encouraging artists and audiences to move on from a mindset that marginalized their own work. In shifting the orientation of artistic creation, he changed the situation of art in the Southern Cone from being derivative to original, from au retaudaire to vanguard. His inversion of positions equally inverted hierarchies and expectations in art, prioritizing art created in South America over art created in Europe and North America.

Just ten years earlier, in 1925, the South American Mission had been opened in Buenos Aires, Argentina by Melvin J. Ballard. At that point in time, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was nearly a hundred years old and had spent most of that time proselyting in Europe and the Pacific. The Mexican Mission was nearly fifty years old. South America was a relative latecomer to the work of the Church. But it didn’t need to remain an afterthought.

Both the founding of the School of the South and of the South American mission mark similar inflection points. These events changed how South America viewed itself and how the rest of the world, particularly the Church in the United States, viewed South America.

In 1996, sixty-one years after the dedication of the South American Mission, Chieko Okazaki gave a General Conference address titled “Baskets and Bottles.” She began her talk by acknowledging another global inflection point: The number of Church members living outside the United States now exceeded that of those living in the United States. South America was a major driver of this shift. Today, about one out of every four Latter-day Saints lives in South America. One out of every six lives in Mexico, Central America, or the Caribbean.

Okazaki’s talk masterfully illustrated the important distinction that Church culture needed to make between the truths of the gospel and the cultural packaging containing them. Okazaki held up a basket of tropical fruits, noting that in Hawaii fruit grows year-round, and people only need to pick enough to last a few days. She contrasted that with a bottle of peaches from Utah, packed and preserved to last through a snowy winter. Then she asked:

Is the bottle right and the basket wrong? No, they are both right. They are containers appropriate to the culture and the needs of the people. And they are both appropriate for the content they carry, which is the fruit.

For too long, the container and the contents have been confused by many members of the Church. The Church was restored in the United States and was subsequently embraced by hundreds of thousands of people from Europe. As a consequence, many cultural traditions arose in the Church that felt comfortable to and served the needs of those first members from North America and Europe. Latin America as a belated field for proselytization, with cultural traditions that appeared foreign and were sometimes labeled as lesser or “wrong,” presented a locale that was simultaneously familiar and alien. This is perhaps best summed up with some of the descriptors used by members of the Church like: the languages are too weird, it’s too Catholic, too indigenous, too dangerous, or just too far south.

In the spirit of Sister Okazaki, we should ask “Is the bottle right and the basket wrong?” Is English right and Spanish wrong? Is square dancing right and samba wrong? Is homemade wheat bread right and arepas wrong?

When God created the Earth, He created a rich tapestry of landscapes and environments, and He declared this to be good. As people have spread throughout the world, they have grown and changed by coming into contact with other peoples, animals, plants, languages, religions, and cultures. Our diverse mortal experiences matter deeply from an eternal perspective. The diversity we live with here on Earth is not a mistake or a problem. It is a blessing and an opportunity.

When we dismiss or ignore the stories of others in the world, we miss a vital opportunity to become like our Heavenly Parents and to more fully love others by seeing them clearly and embracing them in all their complexity.

This leads me to think of some of the stories of Latin American Church members that I have met in the United States. Many of them have testimonies forged from experiences that the average person in the United States has never lived through. The war chapters in the Book of Mormon read differently when you have lived through civil war and violence in your home country. The missionary experience is different when you are an undocumented immigrant still learning English and having to combat racial prejudice from mission companions. The quiet woman who sits in the back of the chapel was exiled from two South American countries due to oppressive dictatorships and then fled to Europe as a political refugee before coming to the United States. She still struggles with English because it is her fourth language.

At the same time, I also want to avoid the trap of presuming that members of the Church who are not from the United States have special wisdom to impart to the rest of us or that their experiences are all uniquely different and incomprehensible. Latin America is a vast region filled with many cultures, languages, and rich socio-cultural diversity. Members of the Church in Latin America struggle with the same challenges as members of the Church throughout the world: family dysfunction, addiction, mental and physical health problems, financial difficulties, spiritual concerns, unrighteous dominion, family members leaving the Church, and the conflation of culture and doctrine.

However, none of these stories can be read if they are not published. Just as English-speaking members of the Church have been creating and publishing literature for nearly two centuries, Mormons all over Latin America have also been busy creating their own literature over the last century. Some of it has been published—both in local Church publications and in non-Mormon venues—and some is still waiting in notebooks or computer files. Fiction, poetry, hymns, and essays are not just the province of English-speaking members of the Church and never have been. However, the dissemination of these stories has always been a challenge.

This is not just a problem for Mormon literature. The flow of literature between the global north and Latin America has primarily been unidirectional. Very little translated literature makes its way back north in comparison to the amount that flows southward. Unfortunately, the Church and Church culture are not different in this respect. The dominance of the Church’s United States-based correlation, translation, and publishing departments, as well as the similar location of non-official publishing ventures, make it difficult for non-English-language literature to find its place in the core of the Church.

Despite these challenges, a global Church should have a global literature. One hundred years after the establishment of a mission in South America, there are nearly seven million members of the Church throughout Latin America, and they all have stories to tell. There are a number of organizations working to support Latin American authors and publish their work. Some of the Latin American organizations pioneering this work include the Cofradía de Letras Mormonas, Ulterior Editorial and its associated Taller de Formación Literaria, and the Asociación de Escritores SUD de Peru. Some of the US-based organizations that have supported the transition include the Mormon Lit Lab and Lit Blitz and the Association for Mormon Letters.

The goal of Torres-Garcia’s inversion of hierarchies was to declare a new priority for the arts and letters of the south, just as Melvin J. Ballard’s dedication of the South American Mission in 1925 opened the doors for a new expansion of the Church in South America. This is, however, just one step on the road to our ultimate destination as a Church. The gospel declares that there should be no manner of “-ites”. This is extremely challenging from our mortal perspective. It’s also one of the central messages of the Book of Mormon—an inversion of hierarchies and a constant reshuffling and questioning of narratives about what it means to be God’s chosen people and how we qualify for the kingdom of God.

When the Savior said to the Nephites “I would that ye should be perfect even as I, or your Father who is in heaven is perfect” he did not mean Asian, European, or even American. Instead, he said that we should be perfect, or in other words, “complete”. For our record as a Church to be complete, we need to publish and read the stories of all of God’s children. To that end, and paraphrasing Torres-García, Latin America, at least in these pages, is our new center, our new north, our new lodestar. In this way, these diverse stories give beauty and variety to the face of discipleship.

“Celebrations” is a newsletter that celebrates sacred moments throughout the calendar and liturgical year. To subscribe to this newsletter, first subscribe to Wayfare, then click here to manage your subscription and turn on notifications for “Celebrations.”

Jessie Christensen is the Romance Languages Catalog Librarian at the BYU Library. She is past co-president of the Association for Mormon Letters, former editor at Segullah, and a writer, editor, and translator.

Art by Joaquín Torres-García (1874-1949).