It is a very fine thing that the full-court press of public debate is now training its attention on artificial intelligence. There are, on the one hand, some real and remarkable advances now available to the interested reader; on the other hand, no less than a simple majority of popular talk about artificial intelligence veers into plain nonsense. Of course, both points go, as it were, hand in hand. We all are sailors already at sea in technology: how can one separate the froth from the current—from the undertow?

I don’t know but here are a few ideas about how not to talk about artificial intelligence.

1. Don’t say “AI,” the mystifying acronym. Instead use the full term “artificial intelligence” once and then specify what you mean: good old fashioned symbolic logic, automatic theorem proving, character recognition, large language models, machine translation, natural language processing, recommendation systems, how people talk about so-called smart technologies, or whatever other application of machine learning, statistical processing, or mathematical reasoning you mean. If someone says “AI” a lot without specification, they most likely don’t know what they mean either: read carefully, avoid repeating precise phrases, and seek meaning that is clear and specific (here’s a low-jargon primer on large language models; here’s a more advanced reading list; a few acronyms may prove useful shorthand among experts but too many acronyms screen off understanding). Keep asking: what does the term artificial intelligence mean in this specific context? Most uses of the term “artificial intelligence” or “AI” have long been, at best, a philosophy that does not know it is philosophy and, at worst, as Thomas Haigh points out, a brand for attracting investment that knows perfectly well but refuses to admit that it is a brand. These misuses are unlikely to change overnight. Be the change: avoid the term artificial intelligence. Be specific instead.

2. Don’t shrug or look away altogether. Don’t dismiss technological consequences. Its civilizational and practical effects are often hard to summarize but worth the effort. (For example, the Haber-Bosch process helped fertilize the food supply for billions in population growth this last century. It also sped gas warfare and climate change in the same. Yet few know about it.) As Melvin Kranzberg famously posited, technology is neither positive nor negative nor least of all neutral. It has effects that are neither only ethical nor only unethical. No emoticon will do. Tech is a plural noun and a complex variable with different consequences for different audiences. To whom do which technologies matter?

3. Don’t follow the hype or freak out. Most tech talk closely follows—and thus stands in for—business cycles and investment talk (AI, in other words, most often stands for “another investment” or “additional investment” or “asking for investment, please” where the please is sneakily quiet). In other words, most tech hype and fear cycles, such as nanotech, Web 3.0, or the new AI from Marc Anderssen, are another way of motivating capital investments. For example, the recent call to pause AI development for at least six months while stakeholders better align human and AI values assumes that such a pause would not give a pass to the unregulated and unscrupulous corporations while the scrupulous pause to recollect. Here’s another example: certain large language models (LLMs) are now scoring well on law school exams. That sounds initially impressive until one realizes that this LLM was trained on the public exam data it is now beating: it is not so “smart” to do the one thing it was trained to do with the data it was trained to do it on. Sensational headlines are written not just to inform but to attract and support private investment, while the applied developers behind those headlines often have more managed expectations. Once we strip away financial interests from public talk about artificial intelligence, what remains often appears out of place or modest. Real change deserves our attention even if we should doubt doomsayers and evangelists as two sides of the same tech hype coin. Who benefits from most AI talk?

4. Don’t buy into one specific future. Don’t lean on analysis that is mostly about the future tense, especially the far future tense. Nothing dates as quickly as a prediction of the future. Here’s my best bet: most futures will be neither apocalyptic nor utopian nor least of all fully predictable. Similarly, discount any analyses that make assumptions of future-tense exponential curves, power curves, and existential tipping points (like IBM on Moore’s law). AI boosters often imitate Disco Stu with tongue in cheek, “just think if this trend continues for decades, nevermind the long term”! Everything fits into the long-term and thus it means nothing: for example, just because an algorithm can analyze contemporary English texts does not mean natural language processing currently or ever will process “language” generally. Of the 6,000 living languages (and tens of thousands of dead languages), only a few receive attention. The surest soothsayers are routinely wrong. Who profits from whose predictions?

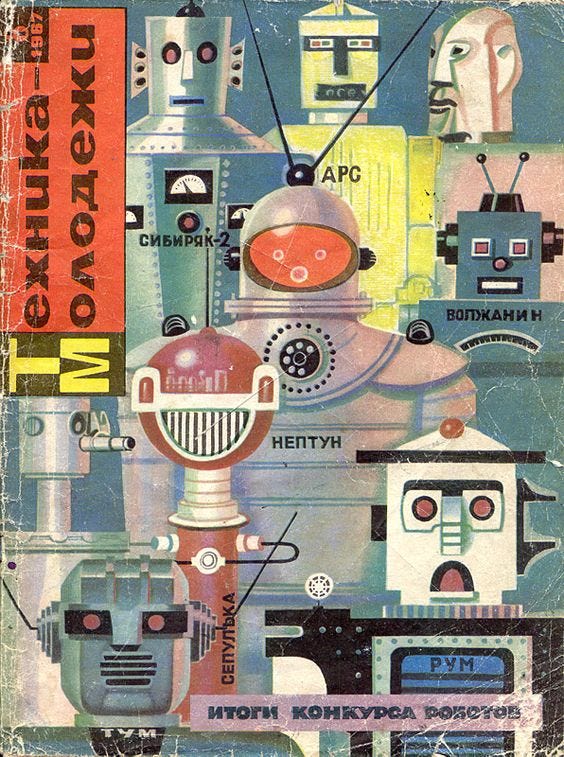

5. On the other hand, be wary of knee-jerk resistance to change; Luddism and boosterism are often two sides of the same team of apocalyptic evangelists, sometimes called the cycle of criti-hype, where industry boosters and Luddite critics reference the same mostly senseless claims. So don’t sell out to the dour naysayers either. The history of artificial intelligence is one of starts and stops: the term “artificial intelligence” was a bit of branding invented in 1955 to differentiate itself from the then dominant paradigm of cybernetics, and thus to attract and secure funding. Nothing new, the term is older than the term “computer science” and has managed to survive uneven multiple funding “winters” (the valleys in the criti-hype cycle) over the last seventy years, although not always for obvious reasons: for example, Geof Hinton’s lab made breakthroughs in the now influential neural network techniques (which were on the books since the 1940s) in large part because the Canadian government kept funding research even when US and British funders chased dead end trends across funding winters. The history of artificial intelligence is humblingly modest: the question is now what will we do with that humility? Cast it aside in our endlessly brave new world or use it to provide context, cautionary tales, and contingencies? History rhymes but it does not repeat, which means we have much to learn from it: in fact, since things are new before they are old, the history of shiny new things that seem historyless is, according to this dated literature review, older than the history of old things.

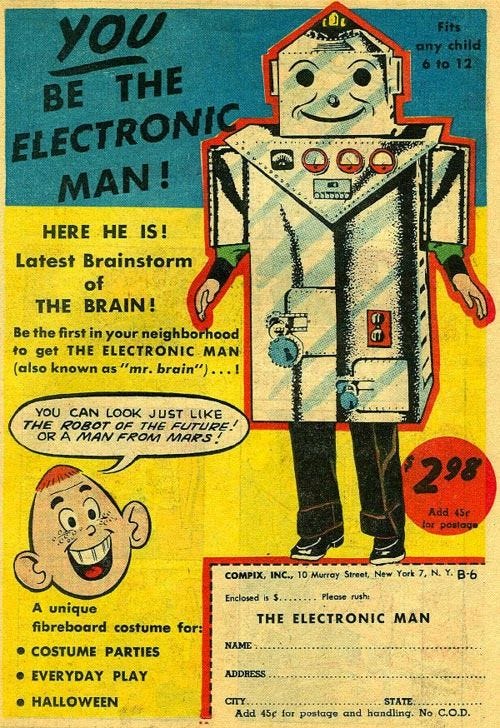

6. Doubt science-fictiony tech anthropomorphism, and check instead real-life humane artifice. AI won’t bring about the apocalypse or the singularity. Smart tech is not created in the image of its creator, despite every metaphor otherwise: technology rarely resembles humans and bodies. Computers are not brains. Neural networks are not neural. Computer memory is different from human memory. Most robots don’t look anything like humans. The uncanny valley is only one site in a wide landscape of the imagination of humans, animals, nature, aliens, and technology.

Rather worry, within reason, about the most canny, practical, and conventional problems: cost-cutting machine translation already is mistranslating immigrant mothers’ paperwork. Consider how humans deform ourselves to respond and serve the emotional affordances and profitable distortions of tech (grief bots, pornography, social media addiction drips, never mind the more than hundred thousand people often poorly paid to shift through the toxic content by hand): these and other industries exploit, prey on, and profit from virtues (mourning, love, attention, labor contracts). These virtues are then fed back and amplified through tech into commodity vices (faux immortality, lust, distraction, labor exploitation). In other words, tech abuses do not follow either people resembling tech or tech resembling people; tech abuse comes from how organizations exploit loops in the modern moral economy. A few profit from, to paraphrase a classic bestseller at the start of this information age, the human misuse of human beings.

Instead of advancing paradigm-shifting, qualitative-leaping terms like superhuman, posthuman, or transhuman, attend to the normal yet meaningful incremental shifts through artifice, technique, and technology that have long defined our modern human species’ historical self-shaping in relationship to its environment. Who cannot spy artificial intelligence-style concerns about the creature displacing the creator dating back to bipedalism and the invention of speech and gesture, the domestication of fire, cave paintings and the rendering of stars above into stories? (AI and celebrity gossip share more than astrological stars in common.) If we glimpse more than human reflections of ourselves in our technology, it is due at least as much to our earthly situation as to any specific new technique or bit of new hardware; it is because through our operations, ideas, and organizations, the modern human continually projects our own images onto nonhumans. Some of those images become healthy, useful, and even saving; some become deeply deleterious, distorting, and narcissistic. Who gains from seeing ourselves where we are not?

7. Listen to and amplify women and other voices often excluded from prominent tech forums, and beware of masculinist and highly gendered visions of machine-driven futures. Tech talk, especially given its proximity to capital-intensive finance and military industries, tends to be run by men trying to reproduce images of themselves by themselves. AI talk fails the Bechdel test so regularly, it is no joke. Check your record of conversation: whose voices are we listening to? Want a few new ideas? Here is some brief context for this list, among just a few more powerful voices. Watch out for uploaded minds, disembodied smarts, and other myths of asocial immortality and its curious variations. Not only gender and race matters: for example, the least accepted student demographic at Oxford, this headline suggests, are working-class young men. Demographic diversity matters indirectly and powerfully: who speaks, and who listens, on behalf of others?

8. Beware long-term predictions. Although sometimes they can yield keen insights, such predictions routinely ignore lurking combinations of entropy, matter, contingency, communities, structural forces, black swan events, and much else that emerge in the short- and mid-term. A three-month prediction may be helpful unless it is chasing a specific quarterly report bottomline; check three-year prophecies against election cycles; check generational predictions against the predicted life arc of the speaker. There is good reason to be wary of many “isms” but note how long-termism, extropianism, singularitarianism, and effective altruism all try to flatten the future into a two-dimensional growth curve. Under the banner of growth, long-term predictions almost always divert attention from current solvable problems in order to focus on abstract existential possibilities that serve the self-interests of organizations not limited by lifespan and ecology, especially powerful corporations and nationstates. Who speaks for the future, and who makes it better?

9. Don’t talk as if tech or AI is immaterial: it is not. Everything about smart tech is material and not all matter is alike. Does this door knob have a lock? Are these atoms splitting or fusing? Does this community enjoy a stable electric grid? Was this edge detector trained on carceral or biased facial recognition data? Such questions obviously matter because tech, while potentially just as symbolic as anything else, is also never immaterial. Note that immaterial claims often pass as those of modern secular religion; for example, this brand new book (click for the free .pdf) explores under-articulated theological implications of AI. Consider the labor injustices in extraction, the uneven scarcities in rare mineral deposits (such as cobalt) worldwide, and the coal powering our handheld devices. Who has pockets to afford such devices? Where do negative externalities hide? What matters to whom, and why?

10. Doubt top ten lists. The most artificial and artful thing in the world is people. We love to invent artful genres—top ten listicles, sonatas, artificial intelligence applications, and other forms for convenient meaning. No expert has the whole truth. Yet, amid the circus of people and machines parroting the hype cycle, maybe we can push pause, look around, take stock of, demystify, use better, and begin rebuilding more responsible talk about artificial intelligence and society: in seeking to do so, this top ten list asks, Whom does AI talk benefit today, and how can we all stand a bit taller?

Benjamin Peters is an Associate Editor at Wayfare and a media scholar. He was first author on this not unrelated list of 9.5 internet theses on the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s 95 theses a few years ago. He is currently writing a history of Soviet artificial intelligence.

Here's a fine resource from the Associated Press on how to cover artificial intelligence:

https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/focus-humans-not-robots-tips-author-ap-guidelines-how-cover-ai